The

Digital Stereoscopic

Renaissance

by Michael Karp, SOC

by Michael Karp, SOC

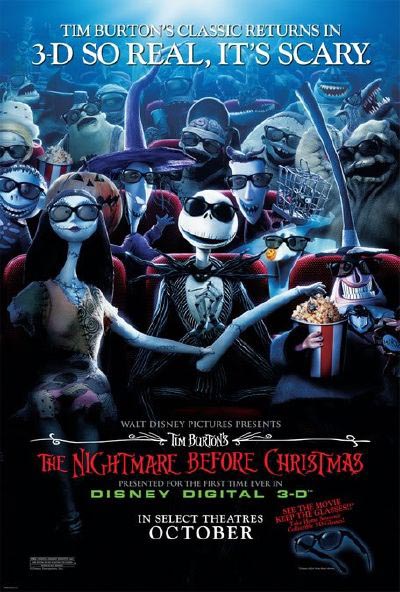

With the artistic and commercial success of Robert Zemeckis's stereoscopic adaption of the epic poem Beowulf, James Cameron's dream of a stereoscopic film renaissance seems at hand. Stereoscopic still photography was actually invented in 1840 and was first attempted for the cinema the 1890s. While 3D cinema has enjoyed several spurts of popularity in the twentieth century, it sometimes has been considered more fad than art, except in special venue/theme park applications. The 1950s produced several important stereoscopic films, as did the 1980s. Since then, Imax and others have been at the forefront of 3D and large format cinema.

But now it looks like stereoscopic film is moving from the artistic ghettos, to the center spotlight of Hollywood production. Important technical improvements, especially in stereo projection, have encouraged auteurs like Cameron to champion the medium.

Let's look at some stereoscopic history.

Most of us are familiar with the cool, five dollar Fisher-Price View-Master 3D viewers long available at many supermarkets and toys stores. Seven stereo color images are contained on a removable disc that one would click through. Home stereo still cameras such as the Stereo-Realist were also introduced in the 1930s.

In the Los Angeles of the 1980s, TV stations would occasionally broadcast stereoscopic movies over the air. We would faithfully scurry off to Wendy's Hamburgers to pick up our red/cyan anaglyph 3D glasses, Obviously these colored anaglyph glasses did not provide nearly the same quality as a full color, theatrical stereoscopic presentation. In the 1970s, Second City TV (SCTV) would make fun of 3D movies. The characters would mockingly create indulgent "3D moments", wave pendulums out at the audience, and romp through fictitious stereo epics such as Dr. Tongue's 3-D House of Stewardesses.

High quality special venue stereo shows are ubiquitous at theme parks like Disneyland and Universal Studios, including Captain EO, Muppetvision 3D and Honey, I Shrank The Audience. But one problem with these special venue shows is that the polarizing glasses that the audiences wore were often quite dark and dingy to view through. The raw 65mm 3D images that we produced at Digital Domain for T2-3D were stunning, as was the Universal Studios live show integrated into the triptych three screen movie. But I always felt a little disappointed when actually viewing the show. If I took my 3D glasses off, the image looked so bright and beautiful, but then of course the stereo effect was lost. When I put the disposable polarizer glasses back on, the stereo looked nice, but the image was dingy again.

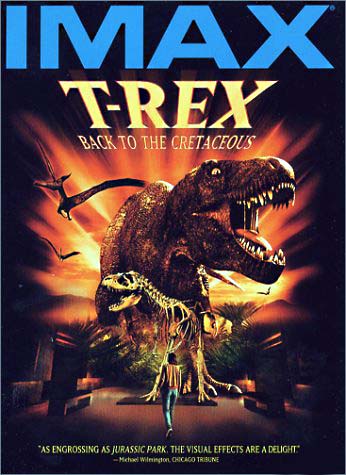

Things improve quite a bit with the Crystal Eyes brand shuttered glasses used on shows like the T-REX: Back to the Cretaceous. But these early "active" glasses were heavy and expensive. And battery charging was a problem for the theater owners.

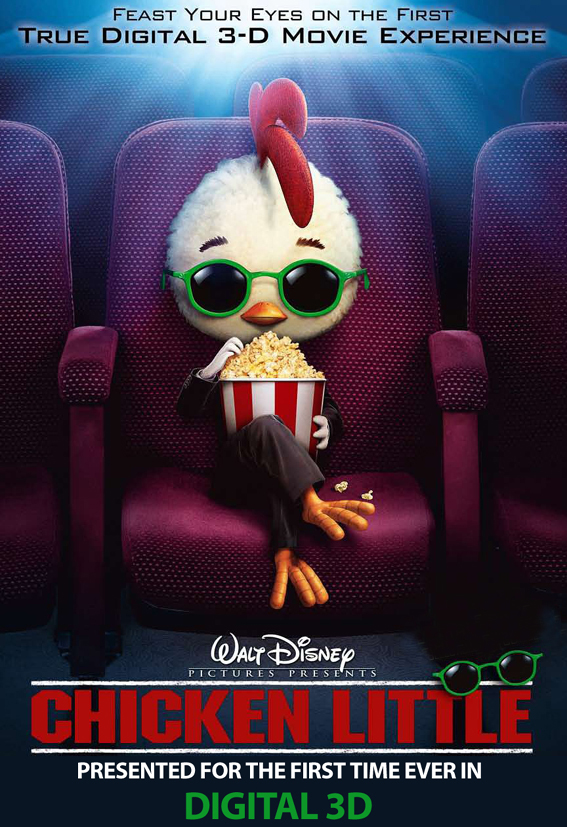

So when Chicken Little - 3D premiered at Disney's flagship Hollywood Blvd. El Capitan Theater in 2005, I was again primed for disappointment. But much to my surprise, the Disney Digital 3D system used was bright and beautiful! The "passive" polarizer glasses were light weight, disposable units. Disney had used the advanced new RealD stereoscopic system, which has helped pave the way for the current stereo resurgence.

Stereo projection throughout the 1980s and 1990s has often been accomplished with large format film projectors, especially Imax. But because of the high cost and complexity of stereo projection and of 65mm film prints, stereo projection was a niche product. And 35mm stereo projection equipment is just as complicated and unappealing to the average theater owner as is 65mm stereo.

Digital stereo projection is different. The Real D system works with very little modification to the existing Texas Instruments DLP digital projectors that are becoming increasingly common even in neighborhood theaters. And because these digital DLP projectors already have a beautiful image similar to film prints (minus film print cost and wear and tear), the combination of Real D stereo and the TI DLP digital projector makes lots of artistic and financial sense for the Hollywood studios and exhibitors. Real D uses circular polarizers instead of the older linear glasses, so the stereo effect isn't lost if the audience member tilts their head. Problems with color casts from the polarizing glasses have also been improved.

Not to be out done, Imax and Dolby are introducing their own digital stereoscopic projection systems for the general public. And Imax stereo analog film projection continues to be very popular.

Digital projection makes sense for another reason. Despite the fact that most digital projection (1k) has much lower resolution than film (2k to 4k), digital projector systems never display film weave. When a film projector is out of alignment and the image shakes (a common situation in real world, neighborhood movie theaters), the film image can look even fuzzier than a steady, but lower resolution digital image.

Many movie theaters suffer from dim images, since their projectors cannot put out the minimum of 12 footlamberts of brightness. Even more light is needed in a stereoscopic system, since most of the stereo glasses lose quite a bit of light.

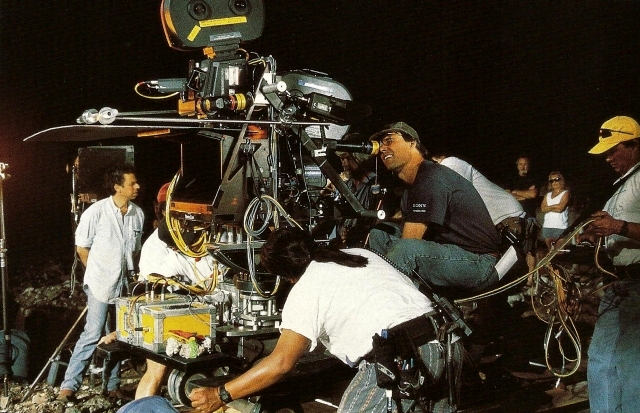

Now that dramatic improvements in stereoscopic projection have arrived, shooting stereoscopic has become easier as well. There are many styles of stereo movie cameras, but the most "artistic" type uses two separate cameras, each looking at right angles into a beam splitter mirror. These camera rigs often look like they were designed by Rube Goldberg and can be very large and funny looking. On T2-3D, we used twin 65mm cameras, which made for a gigantic and heavy rig. Since then, James Cameron and others decided that they wanted to switch to compact digital cinema cameras, especially the Sony F900. These cameras are available in versions with no bulky video recorder built in, so the camera and lens package can be very small. Since the actual video recorder is far away in the video village, the stereoscopic camera rig can then be reduced to a manageable size.

T2-3D dual 65mm stereo

camera rig

|

It is currently possible for the independent or student filmmaker to shoot in stereoscopic, but the process is still much more complicated than regular cinema. Companies such as www.the3drevolution.com, www.kerner.com and www.paradisefx.com can help. But currently, the easiest way for the independent filmmaker to produce in stereoscopic is with an entirely CGI movie. It is not that difficult to add a second camera in Maya, etc. and create the binocular vision of stereo.

However, the process of setting the distance and angle between the left and right stereo eyes is a controversial and arcane art that is still foreign to most filmmakers. Human eyes are naturally 2.5 inches apart (interocular distance), but the interocular of stereo cameras may need to be varied widely based on focal length, blocking, composition, etc. If the distance between the two eyes is too great, the audience will not be able to fuse the two images into one stereo illusion and eyestrain will result. If the the distance between the two eyes is too small, there will be no stereo effect. To better manage this effect, directors such as Cameron will even animate the left/right interocular distance during the individual shot.

The angle between the two cameras is also important. For Imax presentations, it is common to keep the left and right cameras perfectly parallel to one another. But other stereographers prefer to "toe in" the left/right eyes slightly to control stereo convergence, which controls how far out over the audience the stereo appears in depth. This toe in can also be animated during a shot and the interocular and convergence can even be recorded in the digital stream, which assists visual effects artists who may be called on to add special effects to a stereo sequence.

The decision to produce a stereoscopic CGI film is a much easier one than that of producing a live action stereo movie. It is only moderately more trouble to produce a stereoscopic CG film than a monoscopic one. That is why CGI companies like Dreamworks have committed to producing all of their future animated films in stereo. However, live action stereoscopic can be very challenging to create, especially if visual effects are to be added later.

More live action stereo films are coming. Besides event films such as U2 - 3D, Walden Media will be releasing Journey To The Center Of The Earth - 3D and Cameron is shooting Avatar - 3D. Spielberg has also committed to filming in stereo.

Journey

To The Center Of The Earth - 3D

|

But all of this technical talk doesn't answer the vital, bottom line question: Does stereoscopic look good? Is it artistically useful to enhance the storytelling? And don't we all look rather retro in those silly glasses?

I think that almost everyone who has seen the stereoscopic version of Beowulf really enjoyed it. Many reviewers even consider that stereo indispensable to the film and are now sold on the artistic future of 3D. Even without the cool "stereo moments" like the memorable spear shot and the blood dripping at the camera, Beowulf looks great in 3D. When the lights of the theater came up, the man sitting next to me exclaimed that he was dying to have stereoscopic at home. I myself have not yet seen Beowulf monoscopic and I think that it would be very disappointing to view it that way.

So if the stereoscopic renaissance takes off, how far away is the stereo revolution from the home theater? Stereo viewing is already possible with head mounted goggles such as the Headplay Personal Cinema System. And several manufacturers are working on "autostereo" systems, displays which don't require any glasses or accessories for stereo viewing at all. Already, certain home computers can produce stereo images in gaming, especially with nVidia cards and inexpensive shuttered glasses or virtual reality visors.

Headplay

stereoscopic virtual reality goggles

|

The next couple of years will set the pace for the future of stereo cinema, especially the release of Avatar from Jim Cameron. These are exciting days for stereographers and film goers alike. Enjoy the ride.

And yes, those 3D glasses do look cool on you.

P.S. Thanks to Bill Tondreau, Hugh Murray, Nick Ilyin, Max Penner, Jim Cameron and especially Peter Anderson, ASC, for teaching me how this stereo stuff works.

Michael Karp, SOC is a twenty-five year veteran of the motion picture industry. Working as a visual effects CGI artist and vfx cameraman on such blockbusters as Titanic, T2, Apollo 13, X-Men2, True Lies, etc., Michael has pushed the state of the art in that field. He is also an experienced Director of Photography and story development analyst. Michael is a graduate of Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, as well as a longtime film instructor there. He was a match move/layout supervisor on Journey To The Center Of The Earth - 3D, a motion control cameraman on T2-3D and stereoscopic technical director on Ant Bully - 3D.

He can be reached at mckarp@aol.com

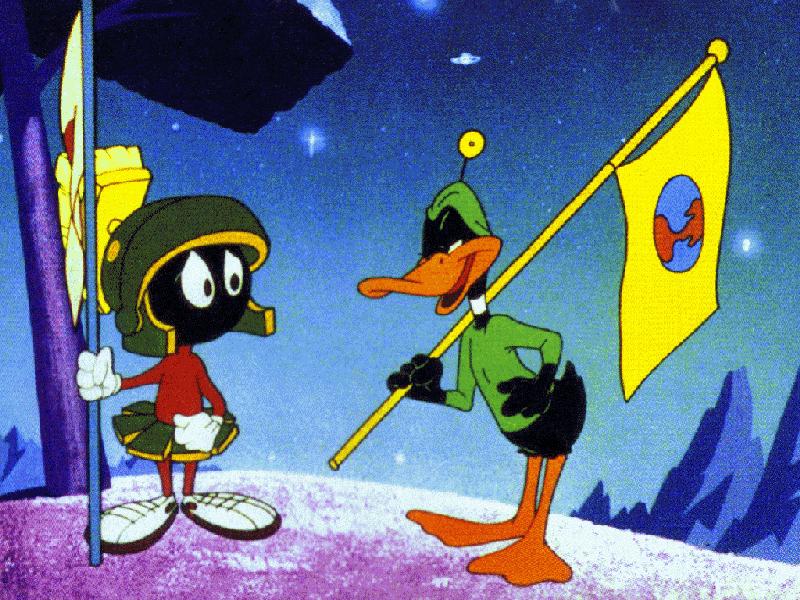

Definitions of

stereoscopic terms: Definitions of

stereoscopic terms:There is confusing jargon used when discussing stereoscopic. The words "2D" and "3D" are ambiguous and I prefer the terms monoscopic and stereoscopic. This is because the expression "3D" really applies to a monoscopic CGI film like Pixar's Cars and the term "2D" usually refers to traditional cell animation like Snow White and South Park. Even more confusing is that 2D cell animation can be shot in stereoscopic, such as Disney did with a Donald Duck cartoon in the 1950s. Shortly after T2-3D, Warner Bros. produced a Marvin the Martian "cell animation" cartoon in stereoscopic, but the entire film was actually created in the "3D" SoftImage CGI package. The film was stereoscopic because two cameras (left/right) were used in SoftImage for binocular vision. The stereoscopic images were "toon shade" rendered, so that they resembled actual "2D" cell animation. The process was very impressive, since a cell animator cannot easily draw in stereoscopic (the stereoscopic Donald Duck cartoon used flat 2D artwork, but was shot stereoscopic with a multi-plane camera). In a computer graphics software like Maya, the artist can actually see the wire frame props and characters from any angle, so Maya is called "3D". For example, if you orbit around Shrek in Maya, you can see the back of his head, the front of his head, etc, even if the final movie ends up being rendered monoscopic. But if we view 2D flat cell artwork of Snow White, it looks fine from the painted front side, but if then we look at the cell image from the back, we can't then see the back of Snow White's head. Thus, traditional cell animation is "2D", even though it can be shot multi-plane or stereoscopic. |