A bitter pill to swallow

Globe and Mail Update

Proposed changes by Ontario to reduce the price of generic drugs will kill a business model the pharmacy industry has relied on for decades

The pharmacy at Lovell Drugs in Oshawa, Ont. is a beehive of activity on a weekday morning. No bigger than a studio apartment, there are seven people behind the counter working in tight quarters, meting out pills.

Before the day is done, they will fill 300 prescriptions, about one every two and a half minutes. There are three pharmacists on duty, along with three pharmacy technicians to help fill bottles and blister packs with drugs, and a cashier to ring through the purchases.

From this huddle of white coats, Rita Winn emerges wearing dark-coloured business attire that sets her apart. A pharmacist by training, she is also the general manager of Lovell Drugs, a chain of 11 small pharmacies in Ontario, some tiny enough to fit inside the cosmetics department of a Shoppers Drug Mart.

It's been a tough week for Ms. Winn and her staff. The pharmacy business has suddenly turned into a place of intense mudslinging between drug store chains and the Ontario government in a fight that could soon spread across Canada. Ms. Winn is trying to remain as calm as she can.

"I could see half my stores closing within the year," she says. "And the other ones that survive, it will be a different model."

Proposed changes by the Ontario government to the way generic drugs are priced have left Lovell Drugs reeling, and have pitted pharmacies, led by industry giants Shoppers Drug Mart Corp. SC-T and Katz Group's Rexall, against the province.

The fight with the province over drug prices has exposed a business model that the pharmacy industry has counted on for decades. Ontario plans to eliminate professional allowances - payments that generic drug manufacturers make to pharmacies as an incentive to use their products over those made by a rival drug company.

These payments, which amount to hundreds of millions of dollars a year for the retailers, are how the pharmacy operations of most drugstores make their profits.

But while some drugstores call the payments rebates, the Ontario government says they inflate drug prices, and eliminating them will cut its annual generic drug tab of more than $1-billion in half.

Fuelling the battle over generic drugs is the increasing clout they are playing in medicine cabinets across the country. In the next five to seven years, some of the most-prescribed drugs in Canada will be coming off patent, meaning the name-brand manufacturer will give way to generic versions that can be sold cheaper.

Lipitor, Advair, Crestor and Nexium are just a few blockbuster medicines that will likely be produced in generic form soon, meaning more of the population will be on generics than ever before - and governments will see their spending on generic drugs soar.

Now the drug tussle in Ontario has become a flashpoint for pharmacy owners across the country. Every province is looking at ways of reducing burgeoning generic drug costs as they grapple with a spiralling health tab.

The stakes are highest for the smallest stores - ones like Lovell that do most of their business in prescriptions rather than branching out with cosmetics and electronics departments. These stores rely on professional allowances to cover everything from salaries to heating bills. These small players say they could find themselves out of business.

The bigger players have diversified well beyond prescriptions and traditional drugstore fare, and boosted their profitability with everything from high-end cosmetics to iPods.

"For all pharmacies, it's going to be harder, absolutely," said John Tse, vice-president of pharmacy and cosmetics at B.C.-based London Drugs, the dominant chain in Western Canada. "But if your business mix is purely pharmacy versus other business portfolios then, yes, they will be impacted."

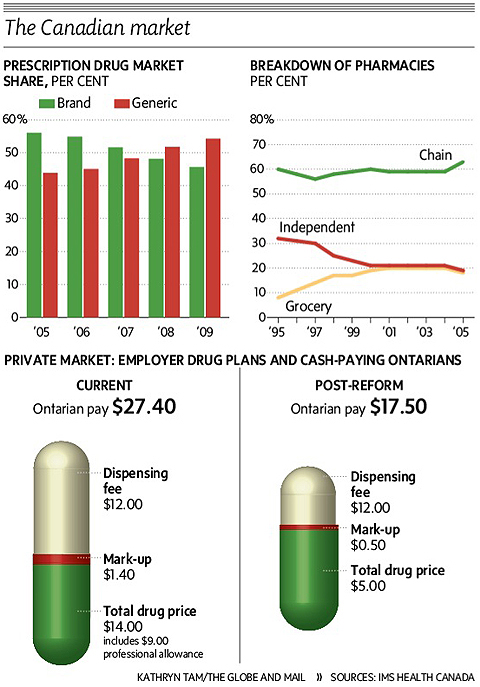

The Canadian market

Professional allowances: An industry game changer

Professional allowances have long been the pharmacy industry's de-facto business model. Governments went along quietly; Ontario waded in with regulations in 2006 that put some restrictions on these allowances and ensured that most of the cash went into helping customers - from free delivery of prescriptions to education programs in the store.

Since the profit margin on drugs is limited by government regulations at about 8 per cent, which mostly covers wholesaling and distribution costs, the payments from drug companies is where pharmacies get their extra profit.

At Lovell, Ms. Winn estimates each of her stores gets about $300,000 annually from generic drug makers, in exchange for exclusively stocking their products. Like it or not, she says, without that money there are no funds to keep operating, since the margin on the drugs is minuscule; dispensing fees - the $10 to $12 that she collects on each prescription of which $7 is covered by Ontario for its public plan - have not been increased in years.

"This store is not an extremely profitable store. Without the professional allowances we wouldn't be able to cover our costs here," she said. "Right off the bat, I'd drop a full-time pharmacist and a technician. So people are going to have to wait longer and they just won't get the same level of service."

The move may also end up pinching consumers. While the cost of the generic drug, covered by public or private health plans, or bought with cash, would go down, the drugstores say they will likely hike their dispensing fees by $5 to $7 at least, meaning more out of pocket expense for consumers.

Deb Matthews, Ontario's Minister of Health, argued that professional allowances drive up the price of generic drugs for customers - and the province is the biggest single customer through its public health plan for seniors and disabled patients.

Last year, these allowances totalled $815-million in Ontario; in comparison, the government spends $4.1-billion annually on prescriptions covered by its public plan, including $1-billion on generic drugs.

Shoppers and Rexall, the two biggest national chains, also warn that the drug reforms will be a hit to their bottom line, forcing staff cuts, shorter hours and longer waits. Already they are rolling back store operating hours and dropping free prescription deliveries and summer student programs.

But there could also be an upside for the big players if the changes spell the end of the small independent pharmacy.

"Shoppers will still be the premier player in a damaged market and should benefit from increased market share and faltering competition," said Perry Caicco, retail analyst at CIBC World Markets. "In fact, as independents are forced to cut back and possibly close, [Shoppers] could benefit over the long term either from acquisitions or shifted business."

At Shoppers, prescription sales make up about half of its sales. Of the bigger drug store chains, London Drugs is also well-positioned to withstand the generic blow, with about 15 per cent of revenue coming from prescription sales - the rest is comprised of everything from computers to big-screen TVs and insurance services.

Katz Group's Rexall and Pharma Plus drugstores and Quebec-based Jean Coutu Group (PJC) Inc. PJC.A-T are more reliant on prescription sales, with roughly 70 per cent and 65 per cent, respectively, of their revenues coming from the pharmacy counter.

"If you have a 50-per-cent reduction in 70 per cent of your business, how do you make it up?" said Andy Giancamilli, chief executive officer of Katz Group, which also is a distributor for independent pharmacies. "You can't make it up. That's why emotions are running high."

A Lovell Drugs pharmacy technician takes a prescription order at the Oshawa location. The independent pharmacy will be hit hard by the provincial government's proposed changes to drug pricing.

The increasing impact of generic drug costs

As generic drugs grow their market share, governments see an opportunity step in and dictate pricing.

Last year, generic sales jumped almost 12 per cent to $6.97-billion, more than double the 5-per-cent growth in sales of branded drugs to $15.86-billion, according to pharmaceutical researcher IMS Health.

Some provinces have tried to tackle the issue of inflated generic drug pricing by controlling professional allowances tied to generic drugs covered by public plans - which represent almost half of the prescriptions in Canada.

A watershed report from the federal Competition Bureau in late 2008 underlined the urgency for change. It found that big pharmacies, and not consumers, are the beneficiaries of the generic pricing arrangements between drug manufacturers and drugstores.

Generic drug makers offered pharmacies rebates of as much as 80 per cent off the wholesale price, to entice them to carry their products, the bureau reported. The average rebate was about 40 per cent, but major chains use their buying clout to get bigger discounts.

But for generic drug vendors, the professional allowances are crucial selling points.

Ms. Winn admits its one of the few ways drugstores choose a supplier. "They're all the same price," she says of the generic drugs, which are made identically. "So as the pharmacist, you pick the one that either you like the person that is calling on you, or you like the reputation of that company."

And the amount a company is willing to rebate, anywhere between 10 and 60 per cent at her stores, Ms. Winn estimates, is often a deciding factor.

The province requires that the allowances are used for activities that directly benefit patients, and pharmacies must submit their spending to be audited each year. But the Ontario government figures that almost 70 per cent gets used for salaries, bonuses and fringe benefits.

The push to rein in rising health-care costs

The Ontario fight has made pharmacies the new battleground in the push to maintain the nation's health-care system - while also trimming deficits.

Governments across the country are under pressure to rein in rising health care costs, with every province except Saskatchewan mired in deficit.

Total Canadian spending on health care reached an all-time high of $183.1-billion last year, amounting to about $5,450 for every Canadian and roughly 12 per cent of the gross domestic product.

And drugs are the fastest-growing area in health care, consuming about 17 per cent of spending, up from 9.5 per cent in 2005, according to the Canadian Institute of Health Information.

Beyond trimming costs for public plans, there's also concern about the rising cost to the private sector.

Industry figures collected by the government and obtained by The Globe and Mail reveal just how lucrative the private drug plans are for pharmacies. One unidentified pharmacy last year collected $6.4-million in allowances from generic manufacturers for four drugs that cost $5.9-million, the figures show.

In one instance, the pharmacy received an allowance that was more than three times higher than the cost of the drug itself.

Of the $1.48-billion that manufacturers paid in allowances to pharmacies in 2008 and 2009, just under 80 per cent, or $1.2-billion of the total, was for drugs not funded by the province. They represent about half of all prescriptions.

The pressures to lower generic drug pricing have spilled beyond the Ontario border. Earlier this year, an insurer in Atlantic Canada went to war with pharmacies there when it reduced by about 5 per cent its coverage of generic drugs.

In British Columbia, the provincial government is giving pharmacies until the end of June to reach an agreement to significantly reduce costs for generic drugs.

"The status quo is unacceptable," said B.C. Health Minister Kevin Falcon. "We are aiming to reduce our costs significantly, and will go to unilateral action, as Ontario has, if forced."

Even before the drug reforms transform the drugstore landscape, chains such as London Drugs have prepared for the changes, partly by moving to automating pill counting, bottling and labelling.

London Drugs, which operates in four Western provinces, has introduced robots to more than half of its pharmacies to take over much of the chore of packaging medications.

Shoppers Drug Mart will have installed automated dispensing units in more than 10 per cent of its roughly 1,200 drug stores by the end of this year.

Still, each machine costs more than $175,000 to purchase and install, with monthly $700 service fees, said John Caplice, a senior vice-president at Shoppers.

For smaller players, an uncertain future

Back at Lovell Drugs, the store lacks the digital cameras and cosmetics that Shoppers, Rexall and London Drugs often sell at their stores.

Diversification for Lovell is a row of chocolate bars near the cash register. Though some of its stores sell gifts, 95 per cent of the chain's revenue comes from prescriptions.

If Lovell can't make the business work without the allowances, it will likely be a takeover target for the bigger players, or shut down entirely.

This week, Ms. Winn and her staff began drawing up a list of services they now provide free, which they may need to charge for in the future. Everything from faxing prescriptions to calling doctors offices comes at a cost, and may need to carry a fee at some point in the future.

It's a model similar to a law office, where every hour of the day is accounted for, with a value attached to it. Ms. Winn says she isn't sure what services to charge for though, but feels the pressure to cover costs without the allowances.

Last week, a teenager came in to get a prescription filled and, as Ms. Winn puts it, "was overmedicated."

The 19-year-old was on six other prescriptions.

"When he came to the counter, I could just tell by looking at him, he didn't understand a word I was saying."

The pharmacy spent about 20 minutes to a half hour on the phone with the doctor and talking to the man about how to manage his medications properly. Ms. Winn admits she's not sure what that time is worth.

Professional allowances would have covered the cost of the pharmacy providing that service, she argues.

"I think the public is thinking, our prices are going to go down, because the price of generic drugs is coming down," she says.

"But if I would say it isn't going to drop the prices, because we're going to have to make it up somewhere."

(A different version of this article ran in Saturday's print edition. This version has been corrected.)