Indian Prime Minister Prods Coal Monopoly

Narendra Modi seeks to boost output by cutting red tape and sparking competition

BEJDIH, India—Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to end decades of crippling electricity shortages and turn this country into a manufacturing dynamo.

Coal India Ltd. is standing in his way.

At the state-run behemoth’s mine here, men still move coal in baskets on their shoulders. At another project, electricity is so unreliable miners descend in a steam-powered elevator. One giant mine that opened last year runs at a fraction of capacity because a rail line to haul its coal is mired in bureaucracy.

Committees and economists have long studied how to whip Coal India, the world’s largest producer of the fuel, into shape. Labor unions and their allies oppose ideas such as breaking the company into smaller units or privatizing it.

Mr. Modi is taking a gradual approach, centered on what officials call the Billion-Ton Plan: an attempt to double the company’s output in five years by stepping up investment and untangling administrative obstacles.

At the same time, he has steered through Parliament a law opening the way for private companies to mine and sell coal, which could eventually end Coal India’s four-decade monopoly on commercial production.

The two-pronged plan typifies an emerging Modi strategy for getting the cumbersome Indian economy to run better: Fix the plumbing first. Worry about building a new house later.

As Mr. Modi’s administration completes its first year, this cautious approach has frustrated some executives and investors who saw his landslide election win last year as potentially transformative. Instead of slashing costly subsidies for food and fertilizer, he is streamlining their delivery. Instead of repealing a law allowing retroactive taxation, the government is wielding it “with extreme caution and judiciousness,” as his finance minister puts it. Indian markets have taken a beating recently after some foreign investment funds were hit with surprise tax bills.

And instead of privatizing state-run companies, the government is playing nurse.

Breaking up Coal India is a “stock-market-friendly but inefficient suggestion,” said Piyush Goyal, Mr. Modi’s coal minister. “Reform, to my mind, is efficiency.”

India’s central government controlled 290 business enterprises as of March 2014. Accounting for more than a fifth of the country’s economic activity, they drill for oil, run hotels and make everything from watches to prosthetic limbs.

The Modi government has reduced state ownership in some of these companies to raise revenue. In January it sold off 10% of Coal India’s shares, netting around $3.6 billion for federal coffers and lowering its stake to 80%. But the focus for now will be improvement, not divestiture, reflecting both the political risks in surrendering state control and the pragmatic core of Mr. Modi’s governing philosophy.

There are no “ideologies for the sake of ideologies” in his administration, said Vallabh Bhansali, a member of a panel that advised the government on energy policy.

Land for factories

Even so, Mr. Modi has taken pains to shed one particular tag: that he is too friendly to big business. His most grueling political test to date has been over his efforts to make it easier for the government to take rural land for new factories and infrastructure, a drive the opposition Congress party calls “anti-farmer.” After weeks of fiery debate, Parliament ended its latest session Wednesday without passing the bill.

The fight shows how carefully Mr. Modi must tune his actions and his rhetoric to achieve even incremental steps. “This is a government for the poor,” he recently told lawmakers in his Bharatiya Janata Party. The government “wants to change the lives of ordinary people.”

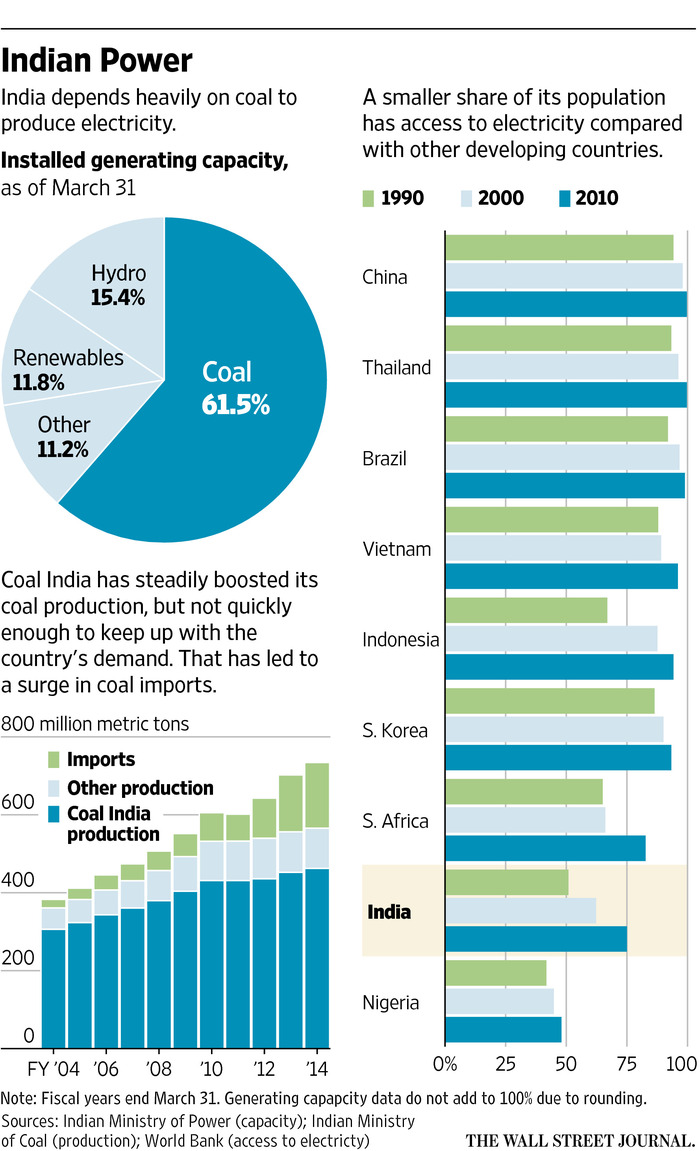

India’s fast-growing economy runs on coal, which means Coal India’s struggles to meet demand have ripples internationally. Coal imports have risen rapidly to about 170 million metric tons a year. As developed countries turn to more environmentally friendly natural gas and as China’s growth slows, analysts predict India will increasingly dominate global coal demand over the next decade.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Summer was fast approaching when Mr. Modi took office a year ago, and with it a surge in electricity demand that annually threatens mass blackouts in India. Some power plants had only a few days’ coal supply on hand.

The day of his swearing-in, he named Mr. Goyal, a onetime investment banker, to concurrently lead three ministries—power, coal and renewable energy—in a bid to reduce bureaucratic friction.

Mr. Goyal visited the formerly Modi-run state of Gujarat, where a government-owned power company had swung to a profit after years of losses. Mr. Modi turned it around without raising prices, Mr. Goyal said: “Only by improving efficiency—and that’s what we have set out to do.”

At Coal India, the task is mammoth. Technology that long ago revolutionized mining elsewhere is only starting to find a foothold in its over 400 mines.

At the underground mine in Bejdih in West Bengal state, workers walk long distances to reach the coal face, through unlit tunnels with low ceilings supported by logs. In an average eight-hour shift, each miner digs around a quarter-ton of coal, an amount that workers at U.S. underground mines can produce in five minutes. The mine loses around $175 on every ton it turns out.

Coal India has 333,000 employees, their positions protected by unions and laws against mass layoffs. The average age is between 45 and 50. A 2011 government report called this force “geriatric.”

Coal India officials acknowledge the laggardly production record but blame external factors. “We have to go through many government rules, many company rules, many regulations, audits,” said Subrata Chakravarty, incoming head of operations in West Bengal.

Most executives cheer Mr. Modi’s hands-on approach and say private competition would help shoulder some of the burden of meeting India’s coal needs, though some say private miners don’t have the requisite expertise.

As for unions, “Workers support more production, more efficiency” so long as health and safety standards aren’t compromised, said Jibon Roy, general secretary of the All India Coal Workers’ Federation.

The root problem, union officials said, is red tape. Acquiring land for mines and rail lines takes years of delicate negotiation.

In Jharkhand state, a mine called Amrapali was inaugurated with fanfare last July after more than a decade of planning and wrangling. Mr. Goyal spoke by video conference at a ribbon-cutting for the open-pit mine, which can theoretically produce 12 million metric tons of coal a year.

After a strong start, it stagnated. With only a rutted two-lane road to haul its output to the nearest rail head 50 miles away, management throttled back production temporarily so inventory wouldn’t accumulate. Coal that sits too long can burst into flame.

Environmental rules have delayed plans for a new rail artery. One proposal failed because the track would have run through forests where collisions with wild elephants were a risk, a company official said.

A mine at Rajrappa, around 60 miles to the east, was among the region’s largest when it opened in the mid-1970s. It is showing its age. Two of its power shovels are at least 30 years old and break down frequently, project manager Sanjiv Kumar said.

In four decades of operation, the mine has never produced at its capacity of three million metric tons a year, and it hasn’t turned a yearly profit since 2005, said A.K. Choudhary, its general manager until recently.

Mr. Goyal, the coal minister, early on began reviewing supply networks so mines would feed only the power plants to which they have good road or rail routes. But he soon found that bigger thinking was required.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

At a meeting with Coal India executives in New Delhi’s government-run Ashok hotel last August, he grew exasperated with slow production growth and poor coal quality at the company. “He was very, very unhappy and very forthright,” said one executive present.

Near midnight, Mr. Goyal declared that to meet India’s energy needs, Coal India had to double its annual output to one billion tons by 2020. “The billion-ton plan didn’t come out of any great calculations—it was in a fit of frustration,” Mr. Goyal recalled.

Hitting the target would require 15% production growth a year. Not all were convinced.

“We thought, ‘He’s a new minister. He doesn’t know the ground-level realities,’ ” said the executive who attended. “ ‘He doesn’t understand what we have to go through to achieve even one- or two-percent growth.’ ”

The next day, as Mr. Goyal lunched with Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, they got some jolting news. The Supreme Court ruled that the way previous governments had granted more than 200 “captive” coal-mining licenses wasn’t legal or transparent. Those licenses, in an exception to Coal India’s monopoly, let large industrial companies mine coal just for their own use.

The ruling threatened to aggravate the coal shortage. But it also gave the government an opportunity to plant the seeds for farther-reaching change.

Though privatizing Coal India wasn’t on the table, Modi administration officials figured they could force it to compete with private miners. So as they drafted an ordinance creating a process for auctioning captive-mining licenses, they slipped in a clause to permit commercial mining as well.

“Competition will make everyone work better,” said Mr. Jaitley. “And the Coal India employees can never complain, because we are not touching them.”

Asked who came up with the plan, he said: “No reform in the government is possible till the prime minister gives his nod.”

Parliament, where Mr. Modi’s party holds a majority in only one of two houses, approved a version of the ordinance in March.

Private mining

Commercial coal mining isn’t likely to start right away. The government will finish auctioning the first batches of licenses before it considers granting ones for commercial mining.

Last fall, as the ordinance was coming together, Mr. Modi named Anil Swarup, a fast-talking civil-service veteran with a knack for getting stuck bureaucratic gears moving, as the Coal Ministry’s top bureaucrat. “If you can set this sector right, the economy will be taken care of,” Mr. Swarup said Mr. Modi told him.

With the billion-ton target in mind, Mr. Swarup hit the road, visiting state capitals to prod officials to move faster on applications for coal and rail projects. He ordered up a vast database describing the problems at each of Coal India’s hundreds of mines and strategies to resolve them.

The company’s board approved the plan in February. Since then, ministry officials have kept close watch on mine managers’ progress. At Bejdih, the mine in West Bengal, manager Gujjula Pullaiah said he gets a call from his supervisors whenever production dips below the targeted 100 tons a day.

During efforts to get environmental approvals for a mine near a town called Belpahar, ministry officials repeatedly called and texted A.N. Sahay, the head of Coal India’s unit in the state of Odisha, urging him to follow up with federal and state authorities. Now, with the approval in hand, the mine can produce three million tons a year more than before.

“That’s how production will increase,” Mr. Sahay said—“one million tons here, three million tons there.”

In the quarter ended March 31, Coal India’s production was up 6% from a year earlier and up 15% from the preceding quarter.

Whether it can reach a billion tons is another matter. “I am quite sure it is impossible,” said Partha Bhattacharyya, a former company chairman.

In February, Coal India said it would invest nearly $1 billion in mines and equipment in the fiscal year that began April 1, up 15% from last year. It plans to spend another $1 billion on rail construction.

Asked how soon commercial players might start competing in Indian coal mining, Mr. Swarup, the coal bureaucrat, said he first wants to see how well private companies do, with the newly auctioned captive licenses, at producing for their own use. Private miners might prove more efficient than Coal India or they might not, he said. “I should not assume. Let’s see how it works.”

Write to Raymond Zhong at raymond.zhong@wsj.com and Niharika Mandhana at niharika.mandhana@wsj.com

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20150522/052215sdemails/052215sdemails_167x94.jpg]](IndiaCoal_WSJ_files/052215sdemails_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20150522/052215gradspeech/052215gradspeech_167x94.jpg]](IndiaCoal_WSJ_files/052215gradspeech_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20150522/052215ukabuse/052215ukabuse_167x94.jpg]](IndiaCoal_WSJ_files/052215ukabuse_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20150521/052115nysubway/052115nysubway_167x94.jpg]](IndiaCoal_WSJ_files/052115nysubway_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20150523/052315ireland1/052315ireland1_167x94.jpg]](IndiaCoal_WSJ_files/052315ireland1_167x94.jpg)